“Oh look! There’s a ballet school in the neighbourhood! You know, I’d always wanted to learn ballet.”

“Why don’t you?”

“…no, really?”

“Yes, let’s sign you up for class!”

10 minutes later, mum had paid for me to attend a term of ballet classes. Thus my ballet journey began, in the most unremarkable and typical of fashions.

Except that I was 24. I was clinically depressed and anorexic.

![How Ballet Helped Me Recover from an Eating Disorder]() It started in university.

It started in university.

I’d taken up my parent’s suggestion that I should study law at the top law school in Australia, leaving my family behind on the shores of Singapore. I had once been a terrible student who felt like a constant disappointment to them and I thought the prestige of a law degree would make my parents proud.

I floundered. The law school was filled with some of the brightest young adults in Australia – children of judges and top lawyers. I felt like a fish out of water, barely scraping through. Everyone seemed to be smarter, having to work half as hard for twice as good results.

I decided to do everything in my power to make up for my perceived inadequacies. I holed myself up in the library, studying, from 10 in the morning until closing time. I read that good nutrition, exercise and weight loss would give me more energy to study and better concentration. So I started walking home from the university, gradually adding daily jogs and circuit training. I changed my diet, eating food that I read would enable my body and brain to maximise productivity. It seemed to work. My grades went up.

But every time my marks improved, they had to be bettered. Anything less it would mean failure; that I had regressed in some way.

My life began to be lived in numbers

…the hours I studied per day, the amount I exercised, the number on the scale, the marks I obtained on every assignment and exam. I started counting calories, keeping my intake to a daily net of 1200. I couldn’t trust myself. I could only trust the numbers. They reassured me that I was being disciplined, and doing everything I could to be as good a student as possible. Any deviation would bring on huge waves of guilt. I stopped socialising. My idea of fun became watching episodes Gilmore Girls or Battlestar Galactica over midnight dinners of bagels and vegetable soup. Even my designated ‘rest day’ on Sundays was spent cleaning my house, grocery shopping, going to a church I didn’t care for … doing anything I considered ‘responsible’.

I did really well at the end of my penultimate year. I was also really sick. My period had stopped for 6 months. I was tired, hungry and cold all the time – even getting out of my chair was an effort. I couldn’t sleep well, and my legs would cramp every night. My bones ached to their very core. I was perpetually dehydrated, despite chugging tons of water to fill the starving ache in my stomach. Sometimes I would look out of the glass windows of the law library late at night and contemplate smashing through them, hurtling 4 stories down until I became nothing.

My parents knew something was wrong, but nobody knew I had an eating disorder because I was neither underweight according to the BMI index, nor was I particularly fixated on my figure – only the numbers on the scale, an obsession that was easy to hide.

I tried to help myself. I stopped counting calories. But these things are harder to climb out of than fall into, and my BMI dropped below 18. Now, finally, the doctors said I had a ‘proper’ eating disorder (they called it ‘atypical anorexia’). My university granted me academic leave. I went home, and began the traumatic process of recovery.

That led me to the ballet school.

There are few young girls on earth who don’t dream of wearing tutu and pink tights.

There are few young girls on earth who don’t dream of wearing tutu and pink tights.

Growing up, my sister and I.were similarly taken with the idea. Our ballet aspirations were vetoed by our mother, who declared that we would probably succumb to the boredom of repeated plies and rond de jambs, and put us swimming instead. As a student many years later, I would treat myself to twice yearly performances of the Australian Ballet. It was even more entrancing watching it when I was 22 then dreaming of it at 2 years old. The cacophony of pointe shoes gently frittering across the stage, the soft tulle of a ballet skirt wafting in a dancer’s wake – it was like entering a dream world, where for 2 hours I could forget all the troubles that were weighing me down, and focus on what was happening onstage.

It was this memory that stayed with me, and sprung back up to the forefront of my mind when I walked past that ballet school. I’d gained few kilograms I needed to get back in the scientifically healthy weight range fairly quickly. I was still, however, as weak and tired as ever. My mother thought an hour of basic barre work would be a welcome distraction that wouldn’t prove too taxing on my still-fragile body. I was ashamed and frightened, but I was also determined to enjoy life again. And so, to ballet class I went.

It was just 4 of us in that first class. Staring into a mirror in shorts, fitted tops and tights being encouraged to pull up your body and hold in your stomach can make a person feel incredibly self-conscious, but not once did anyone express dissatisfaction with their physical appearance.

Most of the time I would be glancing at the clock, waiting for the hour to be up so that I could go home and agonize over food. I had to eat 6 meals a day, so I would have tea before I came – usually a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. But I’d starved myself for so long that I never felt full, and the fear of hunger was just as terrifying as the guilt of eating. At the same time, my brain would tell me that I had to be in class to burn every calorie I could. Whenever there wasn’t ballet on that week, I would struggle to cope without my usual dose of exercise, sometimes breaking down or even throwing a tantrum like a 5-year-old. I had suppressed so many emotions for a long time, and now they were all tumbling out of me.

As the months went by and I grew more nourished, I started to enjoy myself more.

The original group of ladies drifted away, one by one. Even the teacher changed. I was still there. The newer students were closer to my age, vivacious and fun-loving. They were the first group of friends I had made after being home for a year. Ballet became a safe place, where for an hour I could laugh and forget about the darkness that haunted my life. Instead, I could focus on learning and improving every week, in an environment where there were no grades, no pressure to perform. There was no such thing as failing. I was free to learn without worrying about being judged. If someone was having trouble with a combination, our teacher would break it down and repeat it with them, with the rest of us cheering them on. No matter how bad a day I was having, I always had a good time in ballet class.

There were things that I had to learn how to cope with too. Many – if not all – young women had insecurities about their body. I had to learn not to be affected by talk of dieting, weight loss or the size of hips, thighs and waists that came from women whom, to my mind, looked perfectly lovely as they were. I could not control how people thought. All I could control were my own actions, and what I needed was not to lose weight or diet. I needed to get better.

Ballet makes you terribly aware of your body’s abilities.

I learnt that I had awful turnout, low arches, hyperextension, a tendency to overarch my lower back and slumping my shoulders, and a pretty woeful sense of coordination. But then I started to notice other things about myself. I was a hard worker. 80 sautés, a hundred leg lifts, 6 repetitions of the same exercise – whatever the teacher threw at me, I would do. When the other girls were stretching I would prop a leg up on a chair and practice over splits. I enjoyed staying back after class to receive more corrections. Few things were as gratifying to me as learning. I would try everything, even if I was pretty sure I was going to look ridiculous. The worse I was at something, the more determined I was to overcome it. So my turnout wasn’t great or I still sickled my feet in passé position. What was more important was that I was continually working to improve.

I started watching ballet videos and movies, reading articles about dance. From Center Stage to Svetlana Zakharova, I wanted to know everything about this beautiful, exacting art.

Inevitable in all my trippings through the ballet world was the subject of nutrition. In a profession where slim, long lines are prized, there were articles at every turn on what to eat and what not to for achieve maximum athletic performance while keeping excess weight to a minimum. Lean meat, low fat, non-fat, good fat, bad fat, low carb, gluten-free, whole grains, energy bars, kale, chia seeds – so many terms bandied about that echoed the information I’d abused and used to punish my body.

But I wasn’t a professional dancer, I reminded myself firmly. Nor was I trying to be.

It would be terribly incongruous with my reality to try and live like one. Eating like that hadn’t made my body happy, nor was it ever going to. I had not been raised on oatmeal or salads or steaks. I’d been raised in a Chinese household, where food was a communal event and rice, noodles and breads were our happy foods. We’d been eating like that for generations and no one had suffered for it.

My brain was finally nourished enough to think rationally.

I learnt how important it was to eat. Skipping a meal or not eating enough would leave me weak and unable to enjoy myself during ballet, much less learn. I learnt of the unimportance of food as well. My ballet friends were the first people outside of my family whom I enjoyed a meal with – a terrifying experience for any anorexic. There is so much out of your control from the dining location to meal choice. And what if they wanted dessert?! In time I realised it didn’t matter what I ate or how much. What mattered was the company I was in and the time we were enjoying together. I was seeing a counsellor for my mental illnesses, and a lot of terms came up which helped me understand why my brain worked the way it did: high-functioning aspergers, giftedness, perfectionism, OCD. It could be easy to let these labels define me, but in my friends and family were people who saw me only as an individual.

I realised I could eat absolutely anything I wanted, whenever I wanted to. I just had to trust my body. In the beginning of my recovery, I craved fried foods, juicy hamburgers, swirls of cold, creamy ice cream, and hot peanut butter oozing out of thick slabs of toast. This was because my body was in desperate need of high-energy food that was rich in fat and protein. As I got better, eating too much rich food would naturally induce my body to crave simpler, cleaner meals, and vice versa. If I was hungry, I could eat more, and if I wasn’t I could simply eat less. I didn’t have to rely on numbers. I didn’t have to earn enjoyment by suffering for it. It was okay for me to eat. My body didn’t balloon; my weight didn’t skyrocket. Recovery really was as simple as ‘having a hamburger’ – to be able to do so guiltlessly and with pleasure.

On a whim, I decided to a start a online store to sell t-shirts with designs based on all the things I loved – especially dance.

After several weeks of research, I’d contacted a contract shirt printing company, coded a webstore and created some designs on Photoshop. I called the shop ‘Cloud & Victory’, named for my parents. It was meant as something to keep me sane while I finished the last semester of university. I’d spend my free time creating designs and funny graphics, which I would post on Tumblr. I loved the work, and people seemed to like the shirts. I thought maybe I could try pursuing this after graduation. I knew I didn’t want to be a lawyer. I would try it for 3 months, I said. 3 months became 6, and 6 months became a year. I’m still doing it.

Cloud & Victory has become so much a part of my ballet journey. It’s been a gradual, slow process, but through it I have gained confidence in myself, and learnt how to deal with the many challenges that inevitably come. I have been blessed with so many opportunities to meet, work and come to know amazing, inspiring dancers. That they love what I do is so rewarding, and some of them have not only lent me their generous support, but their friendship and their faith – and helped me rediscover my faith as well. You rarely reach the higher echelons of the dance world by beating yourself up, and dancers serve as my inspiration for how to turn perfectionism from a destructive force into something constructive.

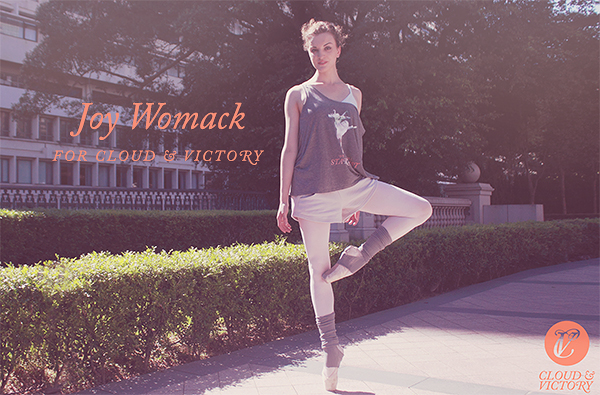

My first work trip was for a Cloud & Victory shoot with two wonderful dancers, Joy Womack and Mario Labrador. The lead up was an exercise in holding myself together – what if I wasn’t good enough? What if something went wrong and I couldn’t handle it? I’d never styled or directed a shoot before, much less with professional dancers! What if I was incompetent, a fraud? It turned out that I could hold my own, and the experience turned out to be a truly fantastic one that I will forever treasure.

I bought myself a white leotard, a beautifully-tailored Degas, when I finally graduated from university. White is infamously the least kind colour on a person’s lines, but I didn’t care. I abhorred dark-coloured leotards, and when I looked in the mirror during class, it didn’t matter that I wasn’t lean and slender, or that I couldn’t get my feet to that perfect 180 degrees alignment. What I saw was myself in the pristine leotard of my dreams.

I knew – I don’t have an eating disorder anymore.

I still have bad days along with the good ones. Though no longer depressed, I still deal with chronic anxiety as I build my self-confidence. The anorexia has left me with anaemia before my period, during which time I have to struggle to complete my work through a haze of fatigue and dizziness. I am constantly trying to balance between working hard without pushing myself to extremities. Recently after an experience which triggered a traumatic memory, my mother found me hiding underneath my bed, sobbing like a frightened child, feeling so hollow and lonely after having released a terrible memory. She didn’t say anything, just held me as I cried. The next day, it was back to work as usual. The pain didn’t disappear overnight, but I knew in time it would. The lows aren’t as low anymore, and they grow fewer and further between. Every day I find new and better things to fill the emptiness that comes with breaking free of the hold this illness has had on me.

I once interviewed a dancer at the Mariinsky Ballet named Xander Parish. I asked him about dancing the role of Albrecht in Giselle, and how to maintain good form in such a grueling role.

“If you’ve prepared well in the studio the classical ballet should take care of itself,” was his answer.

And it struck me that so it is with life. All we can do is work hard, to the best of our ability and when we step on stage – and all the world is a stage, if you believe a certain famous bard – we just have to trust ourselves…and let go.

Min is the owner of Cloud & Victory (C&V), a ballet-inspired, ethical clothing brand. Founded in 2013, C&V has attracted an international following in the dance community, and counts dancers from the Mariinsky, ABT, Staatsballett and Ballet West amongst its fans. When she’s not working on new designs for C&V, she makes funny ballet graphics for C&V’s various social media pages and interviews inspiring, talented dancers for the C&V Sessions blog . Min has been an adult ballet beginner for some years, and has happily survived going on pointe since 2013. She is based in Singapore.

It started in university.

It started in university. Min is the owner of

Min is the owner of